Uncharted brains: expanding beyond existing atlases#

We’ve just released a new digital 3D atlas for the Eurasian blackcap. This marks a key shift for us: beyond providing a common interface for existing neuroanatomical atlases, we are now also building new ones.

This post explains why we’re taking this step, how we’re approaching it, and what’s next.

Atlases are essential, and we need more of them#

The rise of high-quality digital 3D brain atlases over the past decade has transformed neuroscience. BrainGlobe has both contributed to and benefited from this shift. At the core of our ecosystem is the BrainGlobe Atlas API, a unified interface for accessing atlases across species, supporting most of our workflows. To paraphrase a famous quote:

Nothing in BrainGlobe makes sense except in the light of atlases.

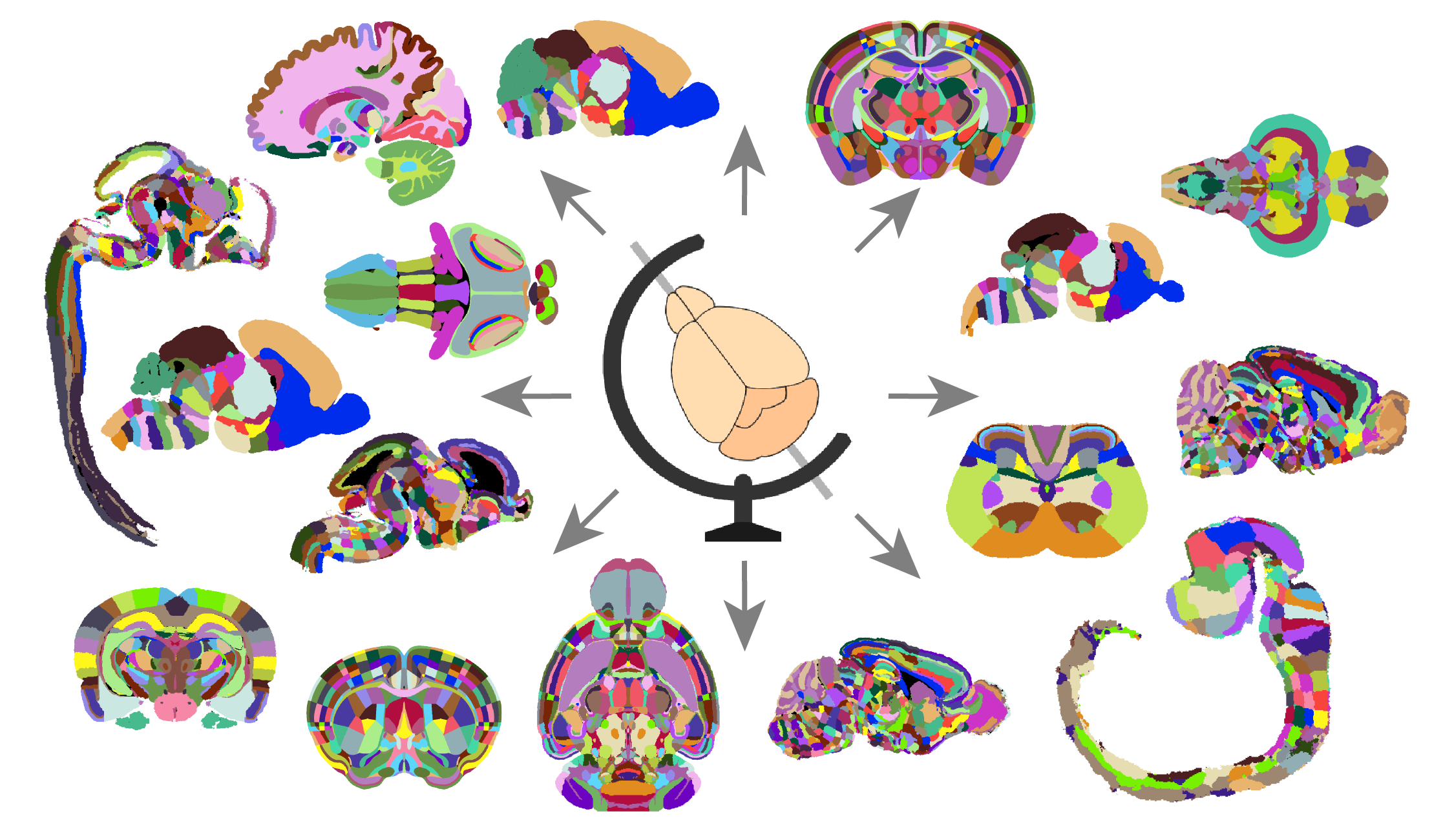

Figure 1. The BrainGlobe ecosystem provides a common interface for a wide range of neuroanatomical atlases across species.#

Atlases help individual researchers plan experiments and interpret their results, but their biggest impact is on the field as a whole. By providing a common coordinate system and standardised terminology, they make data easier to share, compare, and integrate with other sources.

While excellent atlases exist for common model organisms, such as the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas[1] and the Adult Zebrafish Brain Atlas[2], they are scarce for less popular species. Neuroscience is experiencing a welcome non-model organism renaissance[3], but the lack of atlases limits progress. Without a reliable brain map, it is difficult to apply modern neuroscience to emerging models.

This challenge has driven our recent support for species like the axolotl, the prairie vole and the dwarf cuttlefish, with more on the way. However, for most species, atlases either do not exist or lack the resolution and digital precision required for modern brain mapping.

To support neuroscience in uncharted brains, we need more high-quality atlases. But creating them is resource-intensive, requiring advanced imaging, computational power, and neuroanatomical expertise. Given our experience developing BrainGlobe and our access to these resources, we are well-positioned to contribute. The atlas for the Eurasian blackcap marks our first step in this new direction.

Why start with the blackcap?#

A mix of need and opportunity led us to this choice.

The need. Birds possess remarkable traits, one of the most intriguing being their ability to navigate using the Earth’s magnetic field. Migratory birds are key models for studying this phenomenon, yet we lack a high-quality brain atlas for them. Such an atlas is essential to uncover the neural correlates of magnetoreception and magnetic field-guided navigation.

The opportunity arose through Simon Weiler, a postdoc at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre (SWC), where the core BrainGlobe team is based. Simon collaborates with Henrik Mouritsen’s lab at the University of Oldenburg, a group specialising in the magnetic senses of migratory birds. As part of this collaboration, Simon obtained whole-brain samples from Oldenburg and imaged them at SWC using its state-of-the-art serial-section two-photon platform.

The results were outstanding—exceptionally high-resolution 3D images of whole brains, far surpassing what was available for most bird species. Recognising their value, Simon reached out to us about creating a blackcap brain atlas. This would not only help him analyse his data but also provide a valuable resource for the wider research community.

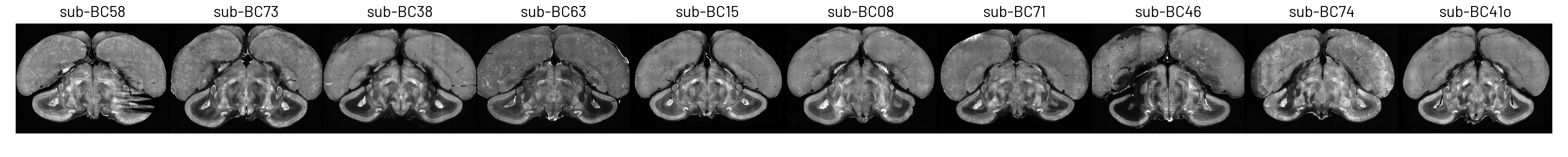

Figure 2. Coronal slices from 10 Eurasian blackcap brains, imaged using serial-section two-photon microscopy.#

How we built the blackcap atlas#

In BrainGlobe, an atlas consists of at least two 3D images:

A template (or reference image) that defines a standard coordinate system for brain anatomy and serves as a registration target.

An annotation image that labels brain structures by assigning integer values to each voxel. This is paired with metadata that maps values to structure names and organises them into a structure hierarchy.

Our first task was to create a high-quality template image. We could have simply chosen one of the 10 imaged brains (see Figure 2), but a single brain may not be representative due to individual anatomical variations. Instead, we opted for a population template, which averages multiple brains to better capture anatomical variability.

We used symmetric group-wise normalisation (SyGN), an algorithm widely used in MRI research to generate unbiased, high-resolution templates for both human and animal brains[4]. SyGN starts with an initial template (e.g., one of the imaged brains) and iteratively refines it by aligning and averaging all input images. This approach minimises bias towards any particular brain, enhances signal-to-noise ratio, and preserves fine anatomical details without the blurring common in simple averaging methods (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The template is refined in both intensity and shape through successive SyGN iterations. The average image becomes progressively sharper as more accurate registrations are applied (rigid, similarity, affine, and non-linear).#

Overcoming technical challenges

Although SyGN is implemented in the ANTs software, we faced several challenges in applying it to our microscopy images:

Different formats and resolutions: SyGN was designed for MRI images, which come in a different file format and typically have lower resolution and smaller file sizes.

Limited sample size: we only had 10 brains due to the difficulty of obtaining blackcap samples (they do not breed in captivity). Two of these had partial damage from sample preparation (see Figure 2).

To address these challenges, we developed a pre-processing pipeline to prepare the data for SyGN. Among other tasks, this pipeline: downsamples the images; rotates them to a standard orientation; converts them to an appropriate file format; masks out the background; removes damaged regions; splits the brains down the midline; and mirrors the two halves to produce symmetric images that guarantee the symmetry of the final template. We implemented this workflow in a Python package, brainglobe-template-builder, which we are working to generalise for broader use.

Running SyGN algorithm on images consisting of tens of million of voxels was computationally intensive. The non-linear registration steps alone required multiple hours per image, meaning a full run could take weeks. Fortunately, we had access to the High Performance Computing (HPC) cluster at SWC as well as an enhanced version of SyGN developed by the Computational Brain Anatomy Laboratory at McGill University. Crucially for us, their version includes the ability to parallelise the computation across multiple HPC nodes and to resume interrupted computations. By configuring this software for our cluster, we reduced the total computation time from weeks to just a few days.

The result was a high-contrast, artefact-free population template with sharp anatomical detail and clearly discernible structures—an ideal basis for annotation.

We shared the final template with our collaborators at the University of Oldenburg, experts in avian neuroanatomy. They manually delineated brain structures using the free software ITK-SNAP. Relying on anatomical landmarks and referencing 2D sections from the zebra finch atlas (a phylogenetically related species), they annotated six principal brain compartments, further subdivided into 13 anatomical regions. Additionally, they also labelled five functionally defined areas involved in magnetoreception, based on prior studies.

Figure 4. Annotated brain structures overlaid on one hemisphere of the average brain template.#

Note

Find more details on how we built the blackcap brain atlas in our preprint[5].

More atlases to come!#

We learnt a lot from creating the blackcap atlas, and we’re eager to apply these insights to future projects. We are already building several new atlases, while streamlining our workflow to make it more efficient and accessible. Some key improvements in progress:

Exploring data requirements for template-building. We adapted SyGN for serial-section two-photon microscopy, but we also aim to support additional 3D imaging techniques, such as light-sheet microscopy. Our goal is to develop a detailed guide on acquiring and quality-controlling images for template construction.

Improving brainglobe-template-builder. We’re gradually making this Python package more modular, flexible, and user-friendly so others can use it to prepare their data for template building.

Further optimising SyGN for HPC clusters. We want to iterate faster and build templates at even higher resolutions, while also sharing these enhancements with the community.

A step-by-step guide for manual annotation. To help groups with anatomical expertise contribute to atlas building, we’re developing a guide on annotation best practices, supplemented with automated quality-control checks to ensure consistency.

Our long-term goal is to scale up atlas creation and empower researchers to map uncharted brains. By expanding the BrainGlobe ecosystem with new atlases, we can help make neuroscience more accessible for emerging model organisms and ultimately accelerate discoveries in the field.

If you are passionate about a species and want to contribute to mapping its brain, please get in touch. We’d love to hear from you!